17 Nov Heads Up – Psychosocial Hazards at Work

Dr Graeme Wright and Claire Halliday

Workers’ compensation claims related to mental health are set to double by 2030, according to the Economic Development of Australia Report 2022. In addition, the report indicated Australian workplaces are faced with the possibility that the median time off work (27 weeks) will result directly from a worker’s mental health compensation claim.

Workers’ compensation claims related to mental health are set to double by 2030, according to the Economic Development of Australia Report 2022. In addition, the report indicated Australian workplaces are faced with the possibility that the median time off work (27 weeks) will result directly from a worker’s mental health compensation claim.

To date, obligations from organisations have primarily focused on physical health and safety in the workplace. This focus has been successful as serious worker compensation claims have decreased over the last few decades. The matters being claimed can be seen, they are obvious, tactile, visible, and accepted as an integrated part of work. This acceptance of an individual’s right to a physically healthy and safe workplace has taken years of training, education, and legislation.

Now there is a new health and safety matter on the block. It must be managed, yet it is not physical, it is not tactile or usually visible. There is no strapping or plaster required and it has been seen in a somewhat negative light within the workforce. Not managing this emerging beast is already costing businesses across Australia billions and it has only just started to be formally recognised.

Corporate Australia is emerging from COVID-19 with quite a few challenges, our biggest being mental health at work. Legislation around providing a psychologically safe workplace is currently dominating a growing number of boardroom discussions. The economic impact is enormous, and organisations are still struggling to work out how to support their staff in managing this critical health matter.

Astute business leaders duty-bound to protect worker’s psychological wellbeing under the current Work Health & Safety Act, are transforming their work environment to ensure staff are safe and healthy at work. In addition, they are taking extraordinary steps to keep employees happy and making huge commitments to attract and retain team members. Yet they are in the minority. One exception is Bellevue Gold in how it went about designing its 343-person camp. The focus in the design of the camp was around feedback from staff on how they saw the camp ensuring a safe and comfortable environment.

Businesses accept that issues surrounding mental health in the workplace can no longer be avoided, but the workplace environment is currently a difficult one to navigate:

- The boundary between work and life has become increasingly blurry since hybrid and remote work took hold – 2.5 million Aussies worked from home on Census Day 2021

- The C-suite are increasingly thinking about life after corporations and the complexities of managing a world post COVID-19

- Psychosocial hazards at work are on the rise with heavy workloads, long hours, unpredictable schedules, social isolation, bullying, and harassment reported as just some of the challenges affecting employees’ health, work and company performance

- 38% of Australian workers plan to leave their organisation in the next 12 months

Whilst the pandemic did not create these work challenges, it has worsened many of them. On top of ‘life’s’ responsibilities outside of the workplace, psychological wellbeing at work when faced with workplace stressors such as dangerous operating conditions, harassment, insufficient training, unrealistic workloads or lack of support, takes on a destructive mix.

Psychosocial hazards and the workforce

Australian Bureau Statistics (ABS) workplace data indicates that 1 in 7 (14.7%) of the Australian workforce experience mental health problems in the workplace. Workplace stress is the cause of 3.2 days lost per worker each year. 25% of the workforce takes time off each year because of stress. 72% of Aussie workers acknowledge that stress impacts their physical health and 64% acknowledge it impacts their mental health. In 2019, the World Health Organisation (WHO) labelled employee burnout a medical condition, noting that its cause is chronic workplace stress. Staggeringly, very few workers seek professional help to manage these issues.

Optimum’s collected data across Australian workforces indicates that between 4%-7% are in the red zones for depression (4%), anxiety (7%) and stress (4%). The red zone response means there is a need for further professional support and intervention. Across the workplace, females recorded double the incidence of red zone responses in all three elements measured.

Pre COVID-19, around 5 million Australians suffered from a mental health condition translating into 10-12 days sick leave. The Productivity Commission found that this cost $39 billion in lost productivity in 2020.

How do psychosocial hazards cause harm?

Psychosocial hazards can create stress.

Stress creates a physiological and psychological response in the body by releasing adrenaline and cortisol, raising the heart rate and blood pressure, boosting glucose levels in the bloodstream, and diverting energy from the immune system to other areas of the body.

Chronic stress can have negative effects on numerous organ systems in the body. Disrupted sleep, increased muscle tension and impaired metabolic function can increase one’s vulnerability to infection, the risk for type 2 diabetes, as well as other chronic health conditions such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, heart disease, obesity, cancer, and auto immune diseases. Chronic mental health can also contribute to increased levels of depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and substance misuse.

Source: Safework Australia, 2022

Top causes of stress at work

- Excessive workload

- Lack of control

- Lack of support

- Senior staff

- Peers

- Insufficient training

- Job security

- Working from home

Managing workplace psychosocial risks

On average, work-related psychological injuries have longer recovery times, higher costs, and require more time away from work. Managing the risks associated with psychosocial hazards not only protects workers, but also decreases the disruption associated with staff turnover and absenteeism. It may also improve broader organisational performance and productivity.

Risk management requires planning and is an ongoing process. However, considering risks early allows for more effective control measures to be used, resulting in less harm to workers.

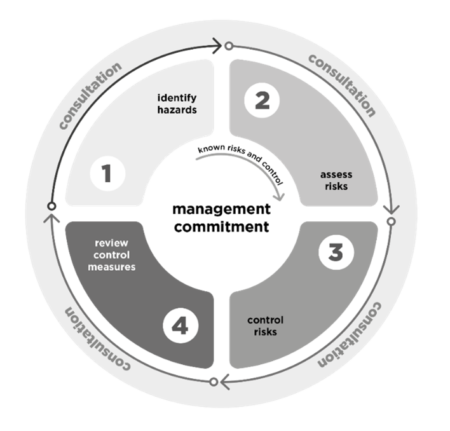

To ensure health and safety compliance, organisations must eliminate or minimise psychosocial risks so far as is reasonably practicable. To achieve this, just as for any other hazard, leaders can apply the risk management process described in four steps by Safework Australia:

Identify hazards – find out what could cause harm

Identify hazards – find out what could cause harm- Assess risks, if necessary – understand the nature of the harm the hazard could cause, how serious the harm could be and the likelihood of it happening. This step may not be necessary if the risks and controls are known

- Control risks – implement the most effective control measures that are reasonably practicable in the circumstances and ensure they remain effective over time. This means:

- you must eliminate risks, if reasonably practicable to do so

- if it is not reasonably practicable to eliminate the risks, implement the most effective control measures to minimise the risks so far as is reasonably practicable in the circumstances, and

- ensure those control measures remain effective over time

- Review control measures to ensure they are working as planned and make changes as required

All these steps must be supported by consultation with the workforce.

Source: Safework Australia, 2022

Meeting your social obligation and responsibility as a business leader

What is becoming evident is that leaders within organisations continue to set the behaviour patterns of employees. There are many ‘implied’ messages sent to the troops in the workplace by leaders. Leaders who work excessive hours, avoid looking after themselves and demonstrate unreasonable workplace behaviours, are not enriching the work environment for employees.

To foster and ensure a safe psychosocial environment, leaders need to set the tone. Furthermore, with legislation now stating workplaces must provide a safe physical and psychological environment for all workers, organisations should provide employees access to resources, training and services that help them manage their mental health at work and better cope with workplace stressors.

How businesses think about, talk about, and cope with all forms of psychological issues is changing. While most employers see mental health as a priority, they struggle to meet increasing employee need and demand for behavioural health services.

How to foster mental health at work?

Creating workplace Mental Health Ambassadors – champions at work. Build a collection of resources that employees can readily access. Ambassadors are available to chat with employees who may be struggling. One company reports that their high performing teams have a corresponding high level of mental health and general wellbeing. This combination ensures a sustainable performance for longer.

Be flexible about what defines the workplace. A company specialising in outside clothing has taken their staff to the outdoors to participate, play, bond and resolve matters while doing physical activities. The group believes the employees learn and grow together. They also retain the energy and joy of a different shared experience.

Offer an integrated Health and Wellbeing Program. Such a program has seen 99% of employees support their business offering such a program, and 99% of them would recommend such a program to their colleagues.

Ban meetings on certain days. One company banned meetings on a particular day of the week. On that day, 83% of their staff reported improved mental health.

Treat Mental Health as an investment. Make it part of not an add on to the working day. Psychologists and health care providers deliver talks. Employees can have a ‘mental health day’ away from the office, without fear of stigmatism.

A four-day working week. This growing bold initiative has seen 98% of one company report better mental health since being granted Fridays off.

Be inclusive. Recognise everyone’s contribution all along the supply chain. Respect at work becomes the norm. It becomes the status quo.

Ask for help. You do not have to do it all on your own.

At work. Redesign jobs, introduce more flexible work practices, increase training and support linked to managing mental health.

The final word

Corporate Australia is trying to get ahead of an increased mental health wave in the workplace. A few years ago, the best some businesses offered was fresh fruit bowls in the crib room and neck and shoulder massages at lunchtime. All this in the name of mental health.

A short-term focus has now been replaced by the need for a longer-term view. It will take years to overcome the underinvestment in psychological safety at work, however if employers begin now, they can earn the appreciation and loyalty of their employees, as well as comply with the new legislation.

It is always tough to act without a clear picture to start with. Things that are measured and receive management attention result in accountability, and workplace mental health is no different. An organisation’s actions will be significant only if business leaders and senior management ensure continuity of effort and follow-through. There must be an overt shift in psychological safety being viewed in strategic terms away from the individual and treatment, to the organisation and prevention.

There is a collective understanding that it is more difficult to address psychological issues in the workplace. It is more complicated. We are all learning about how to get a better set of processes in place. Currently, there is limited guidance available as to how best to handle these matters. It tends to lead to a one-off reactionary response to mental health matters as they arise. A fragmented response does not allow evidence to be gained, nor data collected on what may be the best and most sustainable approach for your business. It also makes it near impossible to evaluate how your business is going in managing mental health in the workplace and how far you may be away from creating a safe psychological work environment.

If you are unsure where to start, explore Optimum’s range of services, including online interventions.

Talk to us and let’s start a conversation.

Sources

Danielle Le Messurier – West Australian, November 2022

Economic Development of Australia Report, Mental health and the workplace, 2022

PWC 25th CEO Survey 2022, The Great Resignation.

Managing Psychosocial Hazards at Work, Safework Australia Code of Practice, July 2022

National Report 2021 – Monitoring mental health and suicide prevention reform. Australia Government, National Mental Health Commission.

Workplace Mental Health & Wellbeing, US Surgeon General Framework, 2022

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2022

Susan Horsburgh – Working towards wellness – Qantas Mag, October 2022

Watkinson Neil – Kalgoorlie Miner, November 2022